Weekly Insights

Young Palm, Palm Canyon, California

Even in February, temperatures in Palm Springs, California, can soar. On one such hot day several years ago, I hiked a favorite path along shaded Palm Canyon Creek. Surrounded by thick groves of California Fan Palms, these ‘trees’ thrive on the creek’s water. On that day, the current flowed at the surface as it usually does during the winter, and the saturated soil beneath the creek bed nourishes them in the dry season.

The steep, rocky canyon lies in otherwise barren desert country east of the 11,000-foot San Jacinto Mountains, the northern terminus of a chain of ranges that form the long spine of Mexico's Baja California peninsula. Palm Canyon is located on the Agua Caliente Band of the Cahuilla Indians Reservation a few miles south of Palm Springs.

The California Fan Palm (Washingtonia filifera) is the only palm native to the western United States, and its largest natural stand is in this canyon. Often described as a tree, the palm is a flowering plant more closely related to grasses. It grows around desert oases such as this stream, fed by fresh snowmelt from the nearby mountains.

The leaves of the California Fan Palm, called fronds, are durable and slow to decay; the Cahuilla used them to make sandals, thatch roofs, and baskets. If not removed by wind or trimmed by human hands, the dead gray-brown fronds will cover their entire trunks, forming, as they do in this canyon, petticoats that shelter small birds and invertebrates. Fallen fronds mat the canyon floor and can easily ignite fires that periodically blacken the palms' trunks and foster reproduction.

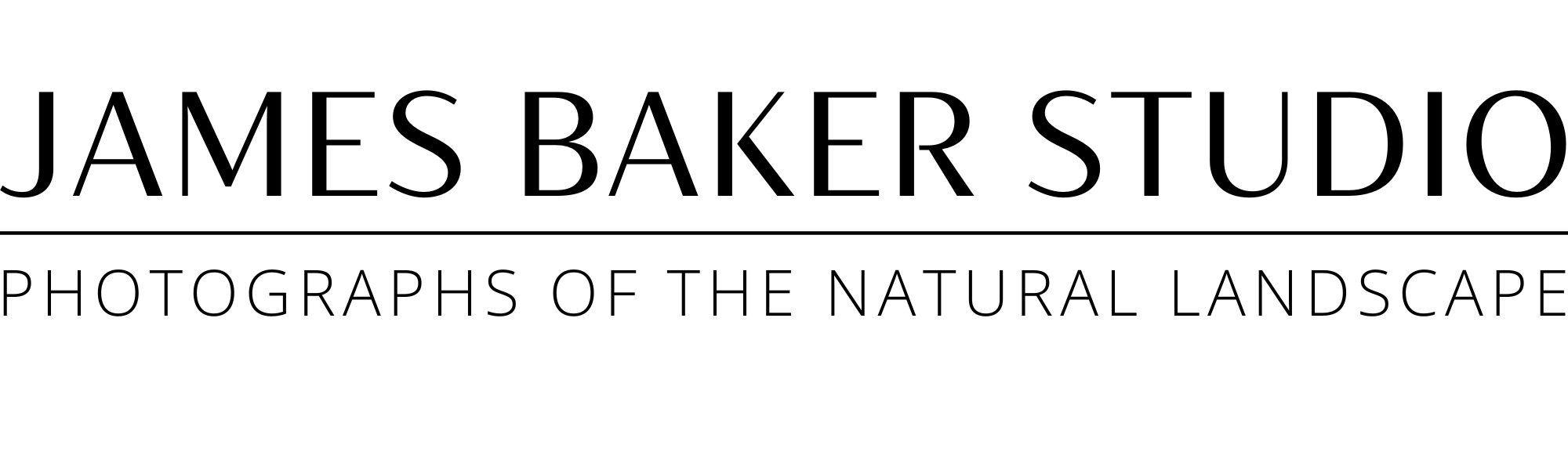

moreDesert Mistletoe, Parashant Canyon, near Colorado River, Arizona

Camping along the Colorado River during the final days of a Grand Canyon river trip, I hiked up a narrow, dark side canyon along Parashant Creek, a short distance from the river. In that early spring two decades ago, the creek, a major yet seasonal tributary of the Colorado River, was already bone dry. Deep in a sheltered ravine, an old mesquite tree grew, its shaggy branches tipped with blossoming buds.

A loosely raveled tangle of green thread, thriving on its ancient host, nestled between its limbs. Mistletoe found in northern Arizona’s Grand Canyon is in many ways very different from the type used for the Yuletide tradition of kissing under the mistletoe. However, all members of the species share one thing: they germinate on and grow directly from tree branches. In the desert Southwest, they attach to acacia, ironwood, and mesquite trees, sending their roots beneath the bark to access nutrients. Its genus, translated from Latin as “tree thief,” can weaken a tree, though it rarely kills it.

Its red-purple berries provide food for birds, and indigenous people used the sweet fruit for food and medicine. While the plant itself is toxic, the desert mistletoe’s berries are edible for humans, unlike those of other varieties, which are poisonous. It also provides nesting for the Phainopepla, a desert flycatcher that is the most common ‘planter’ of desert mistletoe. It eats its berries and quickly processes them, leaving sticky, undamaged seeds on tree branches where it can flourish and grow.

moreNeedle Rock, Dead Fawn, Cape Blanco, Oregon

Descending the field that slumps off the south side of Cape Blanco’s headland, I stepped into a tangled heath. It was late winter when I made this photograph a few years ago, but even at its coldest, the marine climate of this coastal terrace allows the thick undergrowth to thrive, almost hiding a foraging mother porcupine and her two porcupettes. Giving them a wide berth, I came upon another young creature nestled in the grass, a fawn. It looked peaceful, though closer inspection revealed it had died, the cause unknown to me.

While mid-winter is almost always cloudy, wet, and fiercely windy, this late afternoon offered a respite. As I navigated farther down the banked meadow, I saw a bank of cumulus clouds receding south. The sea was relatively calm, the air still and clear, and the sun intensely bright after a storm’s passage. Needle Rock, a sea stack, cast its long shadow across the empty beach.

Etching the horizon, the Orford Reef looked like a school of whales. In fact, it is a cluster of eight small rock islands that provide habitat for marine wildlife, including anemones, fish, sharks, and nesting seabirds. Behind me rose a headland of sedimentary rock that over geologic time, had been rapidly uplifted from the sea. Along this coast, where tectonic plates collide, the floor of the Pacific Ocean pushes eastward into and under the North American continent, raising the former ocean floor 200 feet above sea level to form the state’s westernmost promontory.

moreWater Drop, Ice Storm, Falmouth, Maine

One of the most impactful ice storms in its history hit southern Maine on December 11 and 12, 2008, pelting the region with snow and frozen rain. Power was out for days. Stuck at home, our fireplace kept us warm as we listened to the snapping of limbs and the crashing of trees around us. Power lines hung perilously low or were broken, cluttering streets and sidewalks, and the roads were ice-coated, making it too hazardous to walk or drive.

Ice storms are not uncommon in New England, which is affected more often than other parts of the country. Especially along the coast, where its own weather patterns and occasional cold-air intrusions lead to ice storms. This one began when snow fell through a mile-thick layer of relatively warm air, turning to rain a thousand feet above the ground. Then, a frigid northerly breeze at the surface, accompanying the storm, cooled the ground to just below freezing. Raindrops instantly froze on contact with solid objects.

After it passed and temperatures warmed, I visited the pond at the edge of our property, sitting under the bent and ice-coated willow branches, watching and listening as the water drops hit and then bounced off the pond’s now-melted surface. Using my small digital camera, I captured one drop hitting the pool directly in front of the lens as the shutter clicked.

moreSunset, Chimney Rock, Ute Mountain Tribal Park, Colorado

As I drove along Rt-491 in southwestern Colorado, the light faded from Chimney Rock and the cliffs to the east as the sun set. Just before it vanished, I pulled over and quickly took a series of overlapping shots, which I merged into this panoramic.

In the dying glow, the highlighted pillar and its soft-pastel shadows revealed the scene’s subtle colors and textures. As the day grayed into dusk, it reminded me of how haunting these drylands are at this hour; a very different feeling from earlier, when the late afternoon sun created a dramatic interplay of light, shadow, and color.

Formally known as Jackson Butte, in honor of photographer William Henry Jackson, who documented this region on glass plates in the late 19th century, it is now commonly referred to as Chimney Rock. From a distance, it appears to be a volcanic neck, formed when magma hardens within the vent of an active volcano and later becomes exposed by erosion. In fact, the 900-foot-tall pillar is made of Point Lookout Sandstone, a sedimentary formation found in New Mexico and Colorado. It is lithified sand, a remnant of a beach that bordered an ancient sea that divided western North America. The tower’s base is made of softer, slope-forming Mancos Shale, which originated deep beneath the same sea from clay and mud. As the land rose, these sedimentary rock layers eroded into the plateaus and canyons of today’s red-rock country.

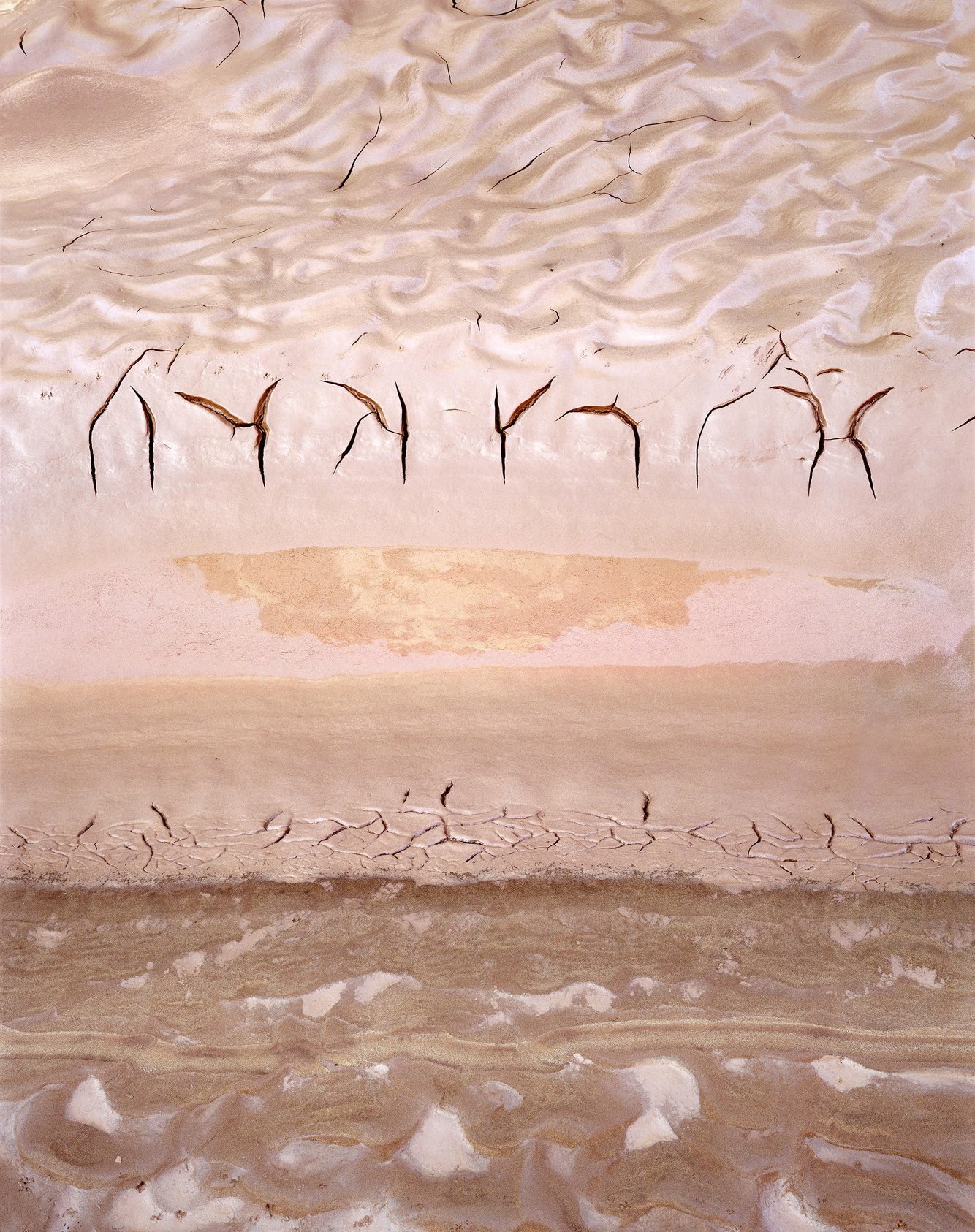

moreFrozen Sand, Provincetown Dunes, Cape Cod, Massachusetts

Walking across the dunes outside the coastal port of Provincetown on a rare, calm, sunny winter morning felt like crossing an arid wilderness, devoid of vegetation, open and flat. This landscape invited me to look down at the patterns in the sand until I came across one that, at first, made no sense. After making this photograph and learning more, I found that, in winter, these dunes are buffeted by winds that move the sand. Snow is often covered with sand blown in from the surrounding dunes and beach. Surface cracks and dimpled hummocks form as the snow beneath alternates between melting and freezing.

Describing the character of this desert, Henry David Thoreau wrote in his 1854 book “Cape Cod,” “None of the elements were resting. On the beach, there is a ceaseless activity, always something going on, in storm and in calm, winter and summer, night and day.” Eighteen thousand years ago, clay, rocks, and sand deposited by receding glaciers formed what would become Cape Cod. As sea levels rose to near present-day levels, the outer part of the cape took on the shape of a forearm. The northernmost reach of the cape (the fist) is where wind and ocean currents transported sand, forming sandbars that are continuously changing in size and height.

moreWinter Sun, Mount Lamborn, Paonia, Colorado

During the winter, winds carry moisture from the Pacific Ocean across several ranges and basins between California and Colorado. When lofted off the dry plateau and pushed up against the abrupt slope of this 11,402-foot mountain, clouds form and congregate above its summit. On the day I made this photograph, a vaporous shroud veiled the sun above the tilted plain. Filtered shafts of sunlight spread from behind a cumulus cloud, resembling a spiritual apparition, and for a moment, conjuring the opening lines of Genesis.

Mount Lamborn is a prominent peak marking the western edge of the Rocky Mountains, a mile above the North Fork of the Gunnison River and not far from the Colorado-Utah border. Ancient upwellings of magma from the Earth’s deep interior created the Rockies. Looking east from the town of Paonia, the rolling foothills of juniper and piñon give way to the sudden ascent of Mount Lamborn’s pyramidal face.

Further east lies a mélange of intertwined ranges stretching 200 miles to Denver, where the Great Plains begin. To its west lie the red-rock canyonlands of eroded plateaus, vaulted arches, and desert rivers. When I lived in Paonia, I enjoyed daily hikes across this threshold (geographically known as an ‘ecotone’) between two distinct geologic and botanical regions, with a mountainous network to the east and vast drylands to the west. Despite living there a decade ago, I still remember how distinctly different the air felt, as I traversed from the desert's dry warmth into the conifer-scented alpine air.

moreDusk, Low Tide, Lincoln Beach, Oregon

Water drains from beneath Lincoln Beach’s bluffs, forming meandering streams that cross the wide sand beach to reach the Pacific Ocean’s shore. The resort city, named for its famous beach on Oregon’s northwest coast, faces west. In this photograph, the water’s edge catches the afterglow of the setting sun during a “King Tide.” Caused by the gravitational pull of the sun’s low winter-solstice angle, a full moon, and the Pacific Ocean’s winter storms, this type of tide rises higher and falls lower than usual. At low tide, more of the ocean bed is exposed, highlighting ripples in the sand left by waves and currents.

The resort, in effect, began in 1837, when two couples arrived by horseback from the Willamette Valley to celebrate their honeymoons, a generation after the 1806 encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, a hundred miles north of this beach. They bathed in the ocean, dug for clams, baked fish, and recorded in their journals that their health improved after several weeks of sun and sea air.

They wrote that they loved the untrammeled feel of the beach. Until then, this part of the coast was inhabited solely by the Siletz, Yaquina, and Alsea peoples. For at least 10,000 years before the newlyweds arrived, settled villages along the river bays and on the ocean thrived in the favorable climate and abundant food sources.

moreSea Ice, Gulf of St. Lawrence, Prince Edward Island, Canada

Damp, windy, and cold are the adjectives that best describe Prince Edward Island's winters. An eastern Canadian province in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, it is renowned for its sublime summers. However, from November through April, sea ice often covers much of the gulf's waters, attaches to its beaches, and coats the cliffs along its coastlines. In fact, Prince Edward Island’s coast marks the southernmost extent of seasonal sea ice in North America.

Edged by sandstone cliffs, inlets, and capes, the miles-long, windswept marine terrace I hiked offered incredible views of a frozen ocean. Thirty years ago, seeing sea ice for the first time was entrancing. I watched it oscillate as gentle swells rolled beneath it, and between visits noticed that ice flows alternately retreated toward the open sea and advanced, piling up against the shore. Sometimes the floating ice gyrated in spirals. Driven by surface winds and ocean currents, this loose, floating field of ice, in effect, traced and tracked the sea surface’s movements.

Fast ice and ice stalactites form a thick layer that encases beaches and cliffs when briny saltwater freezes at 29°F. The offshore slushy drift ice buffers the coastline from winter storm erosion by reducing wave height. Unfortunately, the typical four-month period of protective ice cover has been nearly halved due to warmer winters. If the seasonal sea ice blanketing the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence continues to disappear, the shoreline will erode more rapidly.

moreAA Lava, Volcanic Field, El Pinacate, Sonoran Desert, Mexico

There was no discernible path through this volcanic field in northwestern Mexico's desolate El Pinacate. While traversing this rugged terrain strewn with sharp rocks, I had to climb over and step around numerous cavities, risking getting stuck. My progress was slow and cautious, and with each step, I had to carefully adjust my balance.

An unexpected benefit of my slow progress was that, out of necessity, I had to focus on the details of what became a strangely alluring territory. It felt primal. The Earth's burning interior literally reached out toward space, then was cooled by water and air into a crust. Described as a wasteland, 19th-century European explorers found the Sonoran Desert inhospitable; it was (and to some extent still is) terra incognita to everyone except the Tohono Oʼodham tribe, who hold their homeland in reverence.

Eruptions began four million years ago, forming this region's lava flows and volcanic peaks due to dramatic shifts in the Earth's crust along the San Andreas Fault, less than 100 miles to the west. Multiple times, molten lava moved across the landscape. Its surface solidified into loosely packed, highly irregular fist-sized clinkers (fused, cooled, and hardened lava), while underneath, hotter, fluid magma carried them along.

moreAbove Imperial Rapid, Cataract Canyon, Utah

The Colorado River originates on the west slope of Rocky Mountain National Park. It flows 1400 miles to Mexico’s Gulf of California, although it no longer reaches the ocean due to irrigation diversions. Halfway along its route, the silt-filled river runs through Utah’s deep Cataract Canyon, slow-flowing stretches alternating with, according to its name, white-water cataracts.

This part of the river has numerous rapids, most often dammed by rocks purged from side canyons by flash floods. Further downstream, the Colorado is blocked by Glen Canyon Dam, which, ironically, transformed the lush Glen Canyon into a desert reservoir, Lake Powell.

Twenty years ago, in the early light, I photographed along the riverbank at Ten Cent Camp, where our river trip had pitched tents the previous evening. The new day’s first rays illuminated the canyon rim. In the pooled water above Imperial Rapids, reflections from the canyon walls highlighted mud-coated stones.

From our campsite, I could hear the roar of Cataract Canyon’s final rapid. For many years, it was drowned by Lake Powell. After a severe drought in 2002-3, the lake level dropped, and the arduous chute reappeared.

Of this stretch of river, explorer John Wesley Powell wrote in 1869, “From the edge of the water to the brink of the cliffs it is one thousand six hundred to one thousand eight hundred feet. At this great depth, the river rolls in solemn majesty. The cliffs are reflected from the more quiet river, and we seem to be in the depths of the earth, and yet can look down into waters that reflect a bottomless abyss.”

moreDying Vine Maple with Hanging Mosses, Hoh Rainforest, Washington

On my first visit 30 years ago, when I entered the Hoh Rainforest, I realized that despite the wind, cold, and very wet conditions, late fall is the best time of year to experience western Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. November is one of the wettest months in the Pacific Northwest. It’s when the moss-covered growth of this primeval forest is most alive and vibrant. The drenched air saturated me.

During the short daylight hours of late autumn at this northern latitude, my long drive to the forest made my visit brief. Hastily walking the Hall of Mosses trail, I passed ancient towering cedars, firs, spruces, and hemlocks. On a recent visit, I noticed the forest had thinned; many old giant trees had long since fallen.

At the edge of the grove stood a vine maple, usually about the size of a large bush, though this massive plant nearly reached the height and girth of a tree. In autumn, its leaves turned a strikingly rich shade of orange-red, contrasting with the soft blue-green of the conifers. Its bark was coated with mosses and lichens, lending an ethereal appearance. At the same time, overgrown and tangled, the stretch of its tentacled branches resembled an ominous and brooding creature, ready to reach out and encase me.

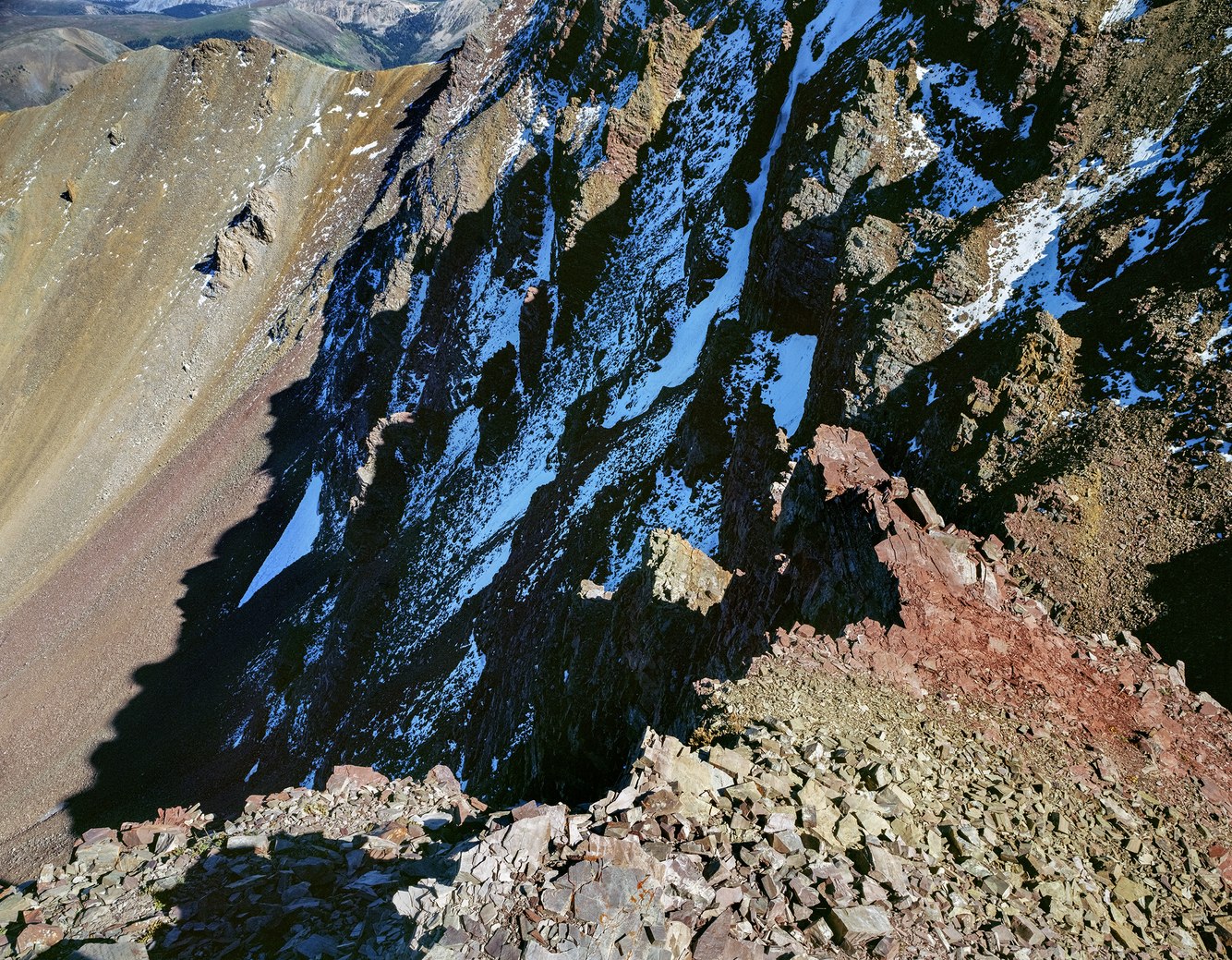

moreMarsh Grass and Glacial Erratic, Nauset Marsh, near Eastham, Massachusetts

Autumn proved to be the ideal time for me to explore Cape Cod's outer shore near the village of Eastham on the eastern arm of the cape. Fifty years ago, in late October, when I visited, summer crowds had long abandoned the beaches. The nights were cool, and the days stayed mild. The colors of warm-hued leaves and meadows deepened as the days grew shorter.

I was drawn to the grass-covered dunes and sea marshes just south of the Coast Guard Beach Lighthouse. Unlike the western United States, which I later explored and initially overwhelmed my senses, in my earlier black-and-white work along New England’s coast, I sought out intimate places where nature revealed itself in unexpected gestures.

Especially in this marsh, where I found a glacial erratic nearly hidden among the wind-blown salt meadow cord grass. Carried over an unknown distance, this boulder was rolled into its smaller rounded shape beneath mile-deep ice, reaching the eastern edge of a continent-spanning ice sheet.

Ten thousand years ago, the glacier left behind a moraine of sand, gravel, and rocks that formed New England’s outermost shoreline. This embryonic erratic appeared as a softly glowing wonder that seemed to have arisen naturally from this brackish basin.

moreTumalo Falls, near Bend, Oregon

Waterfalls are abundant in Oregon, especially in the Columbia River Gorge. They are less common east of the Cascades, where the climate is drier. Central Oregon's Tumalo Creek — whose name comes from the Klamath people's word Tumallowa, meaning "icy water" — is fed by the remnants of a glacier covering the upper slopes of Broken Top. This ancient volcanic cone sits on the crest of the Cascade Mountain Range.

On a cold November morning, I hiked up to the overlook at the top of the falls. The night before, snow had fallen. Later in the morning, the sun broke through, melting the snow on the surrounding plateau and the canyon’s sides. However, the overnight cold settled into the river basin. It preserved a trace of snowfall covering the base of the falls along the stream to the water-diversion dam that provides Bend residents with fresh glacial water.

During the last ice age, glaciers shaped the creek's narrow channel. The 90-foot falls mark the divide between the upper sections of the river that flows down from Broken Top and the flatlands at the mountain's base. The river once flowed higher in cooler, wetter climates. Retreating glaciers and diversions for municipal water to nearby Bend, Oregon, have reduced its flow.

moreLooking Southwest, Mouth of Palm Canyon, Kofa Mountains, Arizona

After climbing the rugged path into Palm Canyon, I turned around to take in the scene. The space between the canyon’s walls opened a window onto the dry, hot desert several hundred feet below. The vista I photographed framed a picture reminiscent of early westerns; B-roll for a John Ford film, with brilliant light from the western plains bleeding into the far mountainous horizon that surrounds this sheltered enclave. It was a stage set, promising a drama ready to unfold, with the appearance of a solitary figure—the lawman or rustler—silhouetted in profile against the hazy desert heat.

These shaded walls of rhyolite, a volcanic rock that easily cracks and fractures into vertical ramparts framing the canyon’s entrance, separated the space I was in, from the flat, expansive La Posa Plain below. A faint track led up through a narrowing ravine briefly sunlit during midday. The slopes featured desert cacti such as saguaro, agave, and cholla, as well as palo verde trees and wildflowers along its streambed.

As an oasis, it protected plant life from the hot, dry Sonoran Desert. The canyon shelters not outlaws but, according to its name, the remnants of a relic species: a grove of rare native palm trees preserved within a cool, moist recess of this volcanic canyon. Descendants of palms that grew in this region during the last period of North American glaciation 10,000 years ago, botanists believe, gradually migrated into this canyon as the climate grew hotter and drier. The canyon serves as an ecological ‘island,’ and with its half-mile-high walls, limited sunlight, and available moisture, the palms depend on and thrive within its unique geography and microclimate.

moreSchoodic Island near Winter Harbor, Maine

The word "Schoodic," a seemingly unique term, may have originated as "Eskwodek," named by the M'ikmaq peoples, meaning "the end" or "point of land." In the mid-19th century, Mark Twain wrote, "The very word schooner is of New England origin, being from the Indian schoon or scoot, meaning to rush, as Schoodic, from scoot and anke, a place where water rushes." Others trace its origins to early northern European roots. Fortunately, all their meanings apply equally to this exposed piece of land where water rushes against the coast.

The view east from The Anvil, a two-hundred-foot granite outcrop, offers a broad panorama of the Gulf of Maine and its coastal islands. It impresses a sense of vastness at the southernmost tip of a peninsula stretching far into the Atlantic from the central Maine mainland. Landfall on Europe's nearest shores is 3000 miles east. In between, the temperamental Atlantic, constantly generating swells, shapes, and erodes this hardened peninsula tirelessly. Initially formed from molten magma deep inside the Earth, it gradually cooled into granite that eventually cracked and, much later, became interspersed with dark, faster-cooling diabase dikes.

One low-lying outcrop of granite, Schoodic Island, lies east of the peninsula. It serves as a nesting sanctuary for American bald eagles and other seabirds—isolated from other wildlife, they can safely congregate. Schoodic Harbor, the deep thoroughfare between the headland and this island, is seasonally dotted with lobster pot buoys checked daily by local lobstermen. On a rare autumn evening, the typically restless ocean takes a respite and lies almost still.

moreNeahkahnie Viewpoint, near Manzanita, Oregon

The road north of Manzanita on Oregon’s northern coast curves around sharp bends high above the ocean. The overlooks can only be fully appreciated when leaning over the edge of the rock walls to experience the full horizontal sweep and vertical depth of the views. Here, waves generated across thousands of miles of the Pacific crash onto the shore in a steady rhythm of breaking swells, where the fog-bound coast meets a radiantly blue ocean and sky.

Oregon’s cold seawater is constantly upwelling, bringing nutrients as phytoplankton. These tiny one-celled organisms have a type of glue that holds them together, and when they die, their skeletal remains release that substance. At the same time, crashing waves push air into this frothy mix, and when it bubbles up, the shore is rimmed with sea foam. Although ocean foam can sometimes be associated with toxic blooms, along this shore, it indicates a healthy ecosystem.

Neahkahnie Mountain—meaning “the place of god” from the language of the Tillamook tribe—is one of the tallest headlands on the Pacific coast. Along the base of this 1,700-foot-high basalt formation ran an ancient trail that, during the 20th century, became a two-lane highway with a line of turnoffs beneath the mountain’s peak, each a few hundred feet above the ocean.

moreMuley Point Overlook, above the San Juan River, Utah

Cedar Mesa, where Muley Point marks its southernmost tip, was once a fertile highland inhabited by the Ancestral Puebloans, who carved homes from caves and cultivated beans, maize, and squash. As the climate dried and warmed about 800 years ago, they moved away from the plateau. Today, campers and hikers explore remnants of an ancient culture in this stunningly beautiful area.

The cliff’s edge where this photograph was taken is fractured by the alternating freezing and thawing of rain and snow, breaking the surface of the plateau into rectangular blocks. These boulders will eventually fall into the shadowed gorge carved by the San Juan River, a major tributary of the Colorado River.

The San Juan was once a slow, meandering stream crossing a nearly flat delta near sea level. Starting a few million years ago, as this plain rose into a plateau, the river carved deep, becoming entrenched in its original path a half mile below this rim.

Between sunset and twilight, the stark land shifts from dun-colored to iridescent hues of red, magenta, and purple. In the distance, the buttes of Arizona’s Monument Valley contour the far horizon. At this time of day, the brilliant sky and somber land blended into one, creating a rare moment in which I felt untethered from where I stood, like in a dream.

moreCirque below East Summit, Mount Sopris, Elk Mountain Range, Colorado

Mt. Sopris is a commanding presence in the Roaring Fork Valley of Central Colorado. Part of the Elk Mountain Range, it rises nearly 7,000 feet above Carbondale. Although it is only of medium height within a range of 14,000-foot peaks, it stands alone, starts from a lower base, and sharply interrupts the horizon line. Its profile might remind one of Japan's Mt. Fuji from certain angles, as it apparently did for a couple (she was born in Japan) who built their home in a location that replicates the mountain’s iconic view.

In truth, it has two summits separated by half a mile, reaching the same elevation of 12,950 feet. Between them lies a cirque, a steeply sloped bowl facing northeast. Sweeping beneath the twin peaks, its shaded orientation makes it ideal for the early buildup of snow that starts to fall at this time of year.

This prominent landmark was created by molten magma rising from deep beneath the Earth's surface. Geologically, the mountain is a pluton, a bulge in the crust formed as the Earth's molten core cooled and solidified, starting around 30 million years ago following the initial uplift of the Rocky Mountains.

While hiking up to the peak wasn’t difficult, footing can be tricky along the exposed mountain path due to loose and crumbling rock, and a few have slipped to their deaths. Along one arm of its western ridge, I took this photograph after a snowfall in the late afternoon of an early fall day, feeling vertiginous, captivated by the nearly vertical landscape of the cirque.

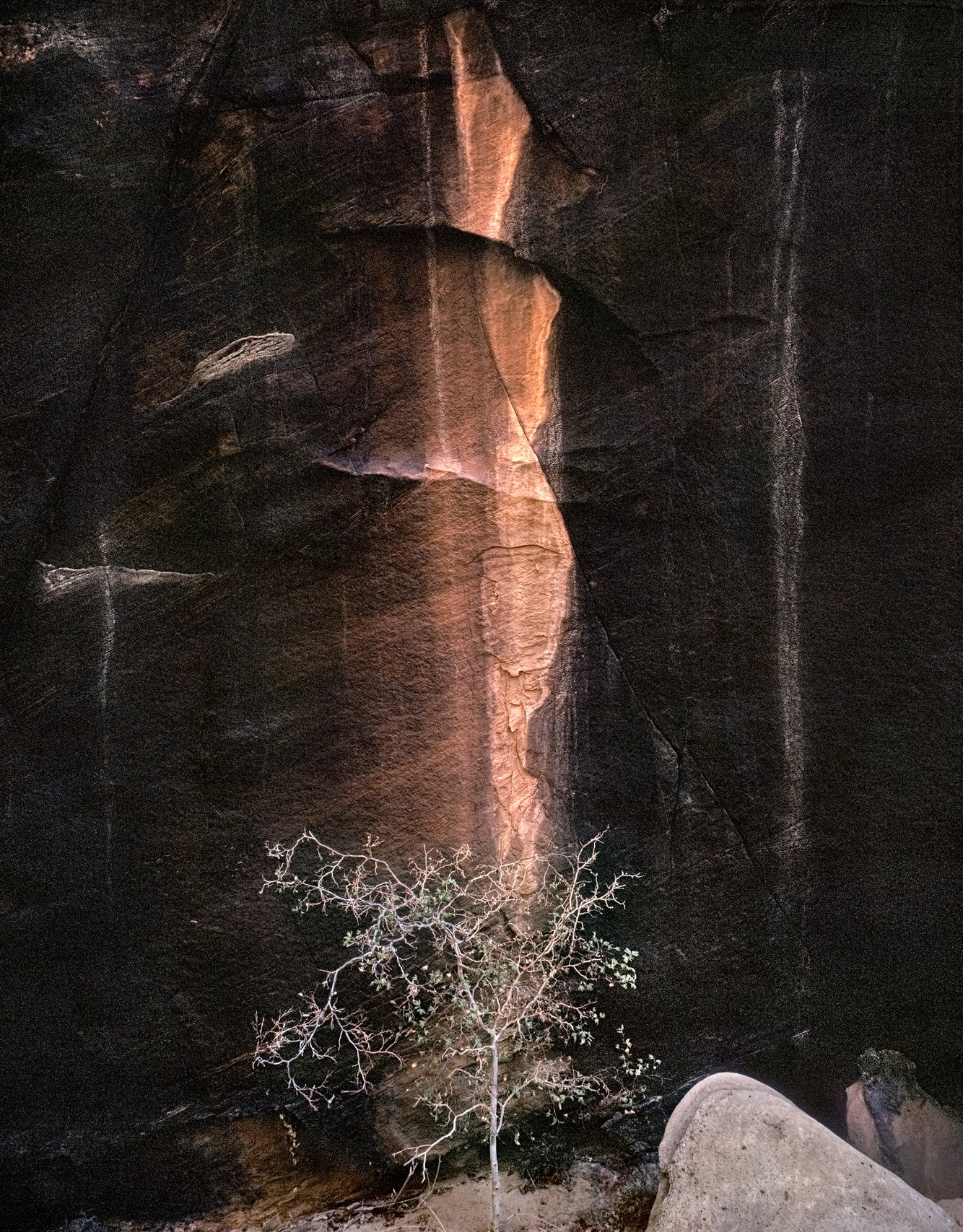

moreBuckskin Gulch, Paria Canyon, Utah

Walking along a trail to Buckskin Gulch, the desert landscape opened into a stretch of grasses, sagebrush, sand, and rocks; then, sloped hills rose around me, composed of splintered sandstone that narrowed into a small path between overhanging bluffs. Finally, I entered an amphitheater at the trail’s intersection with Buckskin Gulch. To my right, a wall displayed desert bighorn sheep petroglyphs around a long curving line chipped into the smooth sandstone, probably incised to depict the gulch’s winding streambed.

My journey was an underground adventure along the narrow base of a deep fracture in the earth. As I ventured deeper into the slot canyon, the walls closed in around me, creating a beautiful yet phobic space that one hiker aptly described as causing “a mild but pervasive sense of anxiety.” At the entrance of this subterranean world, I photographed a muraled rock face of salmon- and yellow-stained sandstone, illuminated by reflected sunlight.

The cross-bedded patterns in the wall revealed the effects of shifting winds that once carried ancient sand into dunes that eventually hardened into stone. The vertical streaks were desert varnish, formed by rainwater and snowmelt running down its surface, depositing thin layers of manganese and iron that tinted the wall in translucent shades of red, brown, and black. Flash floods periodically sweep through the canyon, carrying sand, clay, stones, and tree trunks. The debris level from the last flood was marked by mud splatter, as shown at the bottom of this photograph.

moreDeep Cove, Deer Isle, Maine

Sitting on the shore on this hot New England day, the cool Atlantic water looked inviting. This indentation at the tip of Deep Cove, located on Maine’s mid-coast, has occasionally served as a swimming beach for Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. In this artist community, I taught a photography workshop and captured this image 50 years ago.

Maine seawater is cold, influenced by the Labrador Current’s icy flow, which moderates the warming effects of the Gulf Stream further offshore. The water temperature reaches the high 50s during late summer and early fall. Only a hardy swimmer can challenge the otherwise welcoming ocean. Still, it’s one of the few places along this coast with a beach that extends far enough into the bay to wade despite its ten-foot tidal range.

Low-lying islands draw a subtle line between the cloudy sky and the deep, tranquil Jericho Bay. Spruce and fir trees densely cover Deer Isle, with a vibrant green understory of lichens and mosses fed by the cool, moist air of frequent coastal fog.

The soft dusk light mingles with the transparent water of an ebbing tide to reveal the near shore’s sandy and gravelly till, sediments from glaciers that covered this region 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. More gently sloped than the rest of the steeply ledged shoreline, granite shelves frame this small cove. The clarity of the water and the lightness of the underlying till, reflected by the glow from the late-afternoon clouds, catch the sun’s muted light, giving the cove a brightness. It seems as if one could wade into a bath of light.

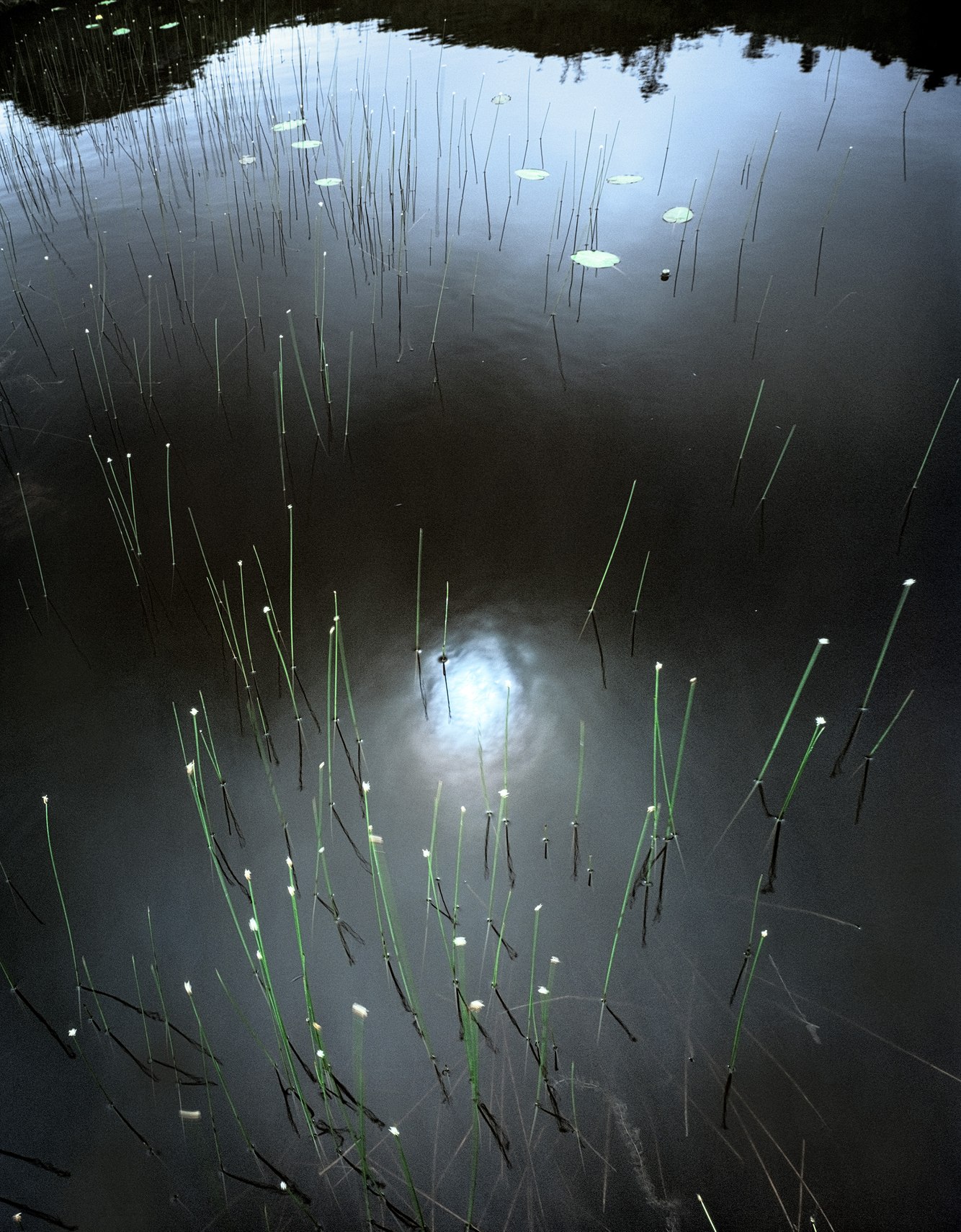

moreDawn, Little Tipsoo Lake, Mt. Rainier, and Yakima Peak, Washington

Surrounding southwestern Washington State’s Mt. Rainier, the high country has been shaped by volcanoes and glaciers. A moraine deposited by an ice flow 11,000 years ago created a dam that formed Little Tipsoo Lake, now a shallow lagoon. Its name is derived from the Chinook language. Throughout Cascadia, “tupso” is used to modify words that describe prairies, meadows, grasses, flowers, and sometimes even hair, all of which aptly describe this stunning meadow. In this photograph, a clump of bunchgrass in the lake looks like a hairpiece for Mt. Rainier’s summit.

Grasses, reeds, and lush fields of wildflowers and berries surround the lake, including huckleberry, lupine, Indian paintbrush, and partridgefoot. Ridges and peaks of the northern Cascade Mountains surround and overshadow the meadow. On their slopes and around the lake are subalpine forests of spruce, rock glaciers, and perennial snowfields. During summer, the lake fills, and although it is fed by snowmelt, it can warm to 70 degrees by August. As summer wanes, the lake shrinks, and during winter, its mile-high elevation is buried under snow drifts as deep as 65 feet until it melts away by mid-July.

At dawn, on the right side of the photograph, is craggy Yakima Peak. During September, the brush and grasses on its south side turn amber, with yellow sagebrush flowers blending with reddish-brown bitterbrush leaves. In the distance, 14,400-foot Mount Rainier dominates the horizon, its peak rising above the gray, corrugated ridge of the Cowlitz Chimneys, a rugged maze of volcanic pinnacles, spires, and knobs.

morePictographs, Canyon del Muerto, Arizona

An alcove in Canyon Del Muerto, Standing Cow Ruin, features a historic hogan—a hut built from rocks recycled from an ancient ruin—smooth sandstone walls streaked with a black patina, and pictographs (paintings on the rock wall) from different periods of indigenous habitation. The canyon is part of a national monument that preserves a record of occupancy spanning at least five thousand years, from the Ancestral Puebloans to the Navajo, who began settling in the canyon in the 1700s and continue to maintain traditions of farming and raising livestock.

This photograph shows part of a wall under a large overhang, decorated with images from various eras. A line of pictographs runs along the lower edge of the image, just above the rock ledges where the artists sat while painting on the rock surface. These white and yellow paintings, probably created by the Ancestral Puebloans in the 13th century, include handprints, concentric circles, and anthropomorphic stick figures.

On both sides (out of view) of this long wall's photographed section are important depictions of Navajo history. To the right stands a Navajo hogan beneath a pictograph of a standing cow and other painted figures and designs, likely created by the families that lived there during and before I took this photo 40 years ago. To the left are pictographs depicting a Spanish procession of horses and armed riders from an 1805 campaign that led to the massacre of over a hundred Navajo. Although named Canyon del Muerto (the canyon of the dead) after the discovery of prehistoric mummies in a nearby cave, the canyon also sadly evokes tribal memories of this 19th-century attack.

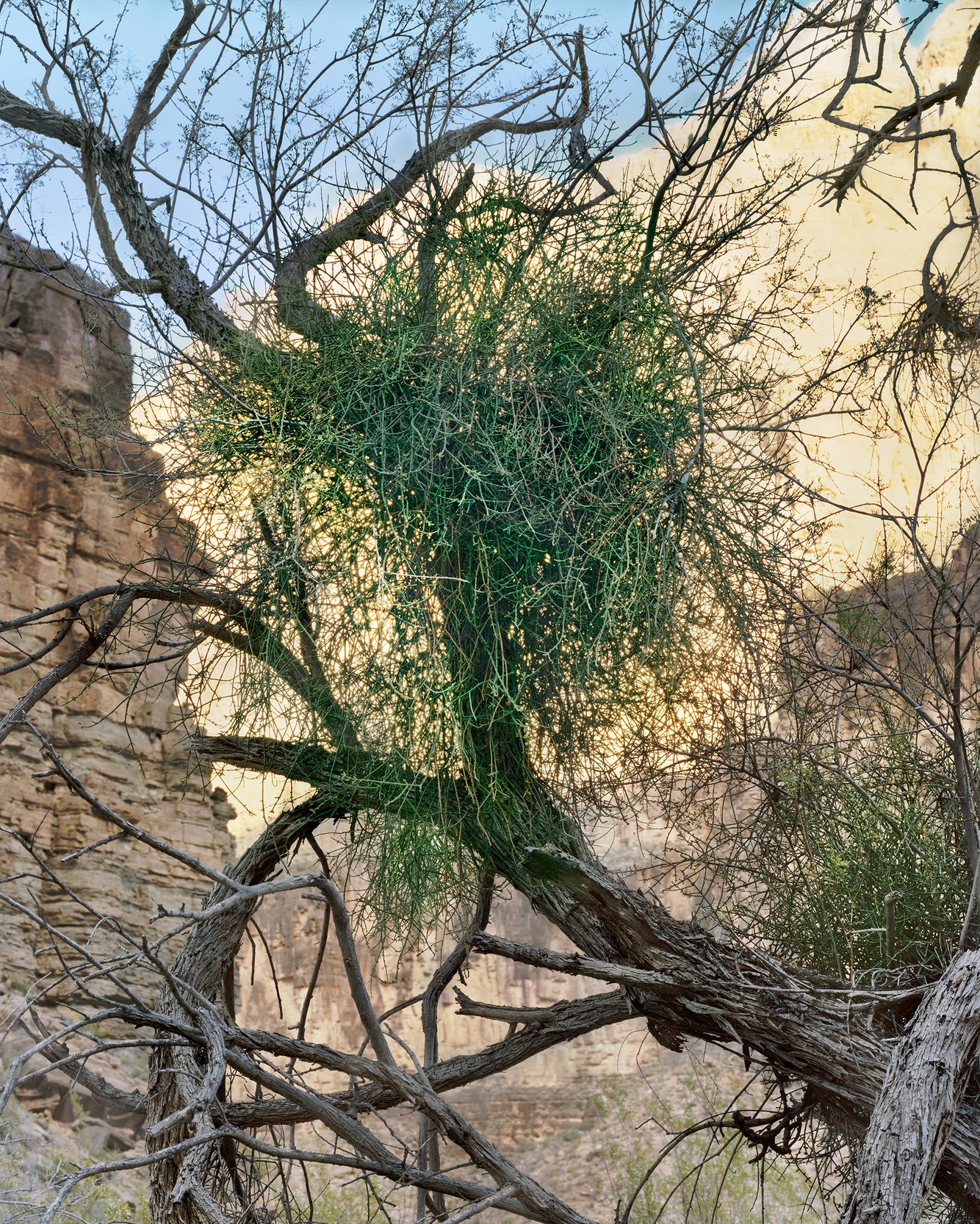

moreSaddle below Electric Pass, Elk Mountain Range, Colorado

The Rocky Mountains formed through repeated uplift and subsidence, contorting and disordering their rock formations. In central Colorado, the Elk Mountain Range outlines the western perimeter of the Rockies. These mountains—mostly above the tree line—were shaped by glacial cirques with narrow ridges separating deep valleys. Maroon-colored sedimentary rocks were uplifted by tectonic shifts in the Earth's mantle to form the range’s peaks.

Summer monsoonal thunderstorms are wetter in the Elk Range than in the mountains to the east, and their 14,000-ft peaks are also more susceptible to electrostatic discharges and lightning strikes. Just above where I took this photograph, Electric Pass reportedly got its name from a ranger in the 1920s who was knocked to the ground multiple times by static shocks before rolling down a slope to safety. On this clear, storm-free late summer day, I hiked the switchback trail safely through meadows and willow stands with easy access to stunning views of the surrounding mountains and their drainages.

Between Electric Pass and Leahy Peak lies a connecting ridge, a 'saddle' at 13,200 feet elevation, where I rested and took this photograph. The foreground features a tapered bench that crumbles and slips down the talus slopes. Cluttered piles of exposed shales and sandstones are part of the stratified, purplish-red, sedimentary rock formed in the Permian era, about 275 million years ago. The season's first snow accumulates in shadowed crevices below the ridgeline, reflecting the deep cyan-blue color of the high-altitude sky.

moreEast Fork, Upper Kaibito Canyon, Arizona

A river traversing a desert might seem unlikely, but there are several, including the Colorado River and its many tributaries. One of these, on the Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona, is Kaibito Creek. This remote seasonal stream is visited less often now than in the past, and even then, visitors were rare. However, rivers are not the only thing that carve through the desert scenery. Hundreds of slot canyons carve into the red rock country of the Colorado Plateau, spanning southern Utah and northern Arizona. Towering soft sandstone walls outline these narrow channels, which are formed and eroded by periodic flash floods from monsoonal thunderstorms.

Slot canyons have become more popular, even in this remote part of the Southwest. However, in 1998, a few years after I took this photograph, the Navajo Nation closed the creek and its canyon to public access due to increased trespassing across their reservation and through residential areas, which had disturbed livestock, led to littering, damaged fragile archaeological sites, and sometimes necessitated dangerous rescues of stranded hikers.

Cautiously, I entered Upper Kaibito Canyon, its upper reaches originating just below a water tank off a dirt road, miles from any town. The canyon's entrance, hidden, even from a short distance, suddenly appeared beneath my feet. I was peering down into a V-shaped crevasse that closed in on itself. Balanced on the steeply sloped sides of this narrow gorge, I placed my legs on either side of the precarious gully. The canyon was deeply shadowed; sunlight bounced off the rim and then, again, off its lower walls, creating a subtle twilight-like glow. In the darkness, barely discernible, the resulting photograph revealed much more than I could see then.

moreView Facing North, Paulina Peak, Oregon

Standing on the summit of Paulina Peak, the first thing that caught my eye was the approaching storm. Soon, rain and hail hammered the cindered ground, and briefly, the wind picked up; lightning flashed, and thunder echoed off the canyon walls. The storm moved north over Paulina and East Lakes before heading into the high desert surrounding this ancient crater.

At an elevation of 8,000 feet, Paulina Peak is the highest point along the rim surrounding the collapsed Newberry Volcano, which formed the caldera shown in this photograph. The peak offers a 360-degree view spanning hundreds of miles in all directions, from Mt. Adams in Washington State to California's Mt. Shasta.

About half a million years ago, the volcano's 14,000-foot summit was roughly in the center of the photograph, above the lakes and the forest basin of lodgepole and ponderosa pine. Today, resting on a thin layer of the Earth’s crust, the caldera remains volcanically active, with several monitoring stations recording ground vibrations and changes in the shape and movement of the terrain in real-time.

To the right lies a tan-gray obsidian field, the most recent geologic addition to the basin. Lava flowed from the rim adjacent to Paulina Peak 1300 years ago and then cooled into volcanic glass. The obsidian boulders are so sharp along their edges that native tribes chipped arrowheads from them. The crater was initially visited by hunter-gatherer peoples beginning at least 11,000 years ago, not long after the Ice Age ended. Today, the caldera is a land of lakes and forests, a place to camp, hike, and fish.

moreKiger and Mosquito Gorges, Steens Mountain, Oregon

Extending north from the cliff where I took this photograph a few summers ago, a sharp divide separates two diverging glaciated valleys: Kiger Gorge on the left and Mosquito Gorge to the right. During a cool, moist climate that lasted from four million to ten thousand years ago, glaciers carved out Steens Mountain's dramatic canyons in southeastern Oregon. Accumulated snow compressed the layers of ice beneath it into thousand-foot-thick glacial flows. These massive ice streams once split in two directions, one flowing north to carve Kiger Gorge and the other moving east down Mosquito Gorge. Their immense weight and downward pressure shaped broad, deep U-shaped valleys. The upper parts of the gorges' walls above the glacial ice are rough and rocky, while the glaciers' abrasive action scoured their basins.

The advantage of Steens’ open and elevated terrain is the opportunity to observe the shape and form of gorges formed of volcanic rock and carved by ice. Its ridge lacks trees, unlike other ranges covered with ponderosa and Douglas fir. Here, where the mountain rises from a low desert base, seed dispersal has not occurred as in other highlands connected by higher ground, allowing tree species to spread from one mountain range to the next.

moreRainbow, Roaring Fork Valley, Colorado

Beginning midday during the high country's summer monsoon season, clouds form, grow, and rise off the shoulders of central Colorado's Elk Mountain Range. By late afternoon, storm clouds fed by sub-tropical moisture and rising heat channel through breaks in the range to the west and over alpine valleys to the east, trailing hail and shafts of rain. As seen from the top of the Brush Creek Valley near Aspen, a final streak of daylight cuts through the clouds, partially illuminating a rainbow before the sun sets.

As sunlight enters each raindrop that makes up the rainbow, it reflects off the interior rear surface back toward the sun, as its angle changes. The light's movement into and then out of the raindrop separates into a spectrum of colors. Each of these colors exits the raindrop at different angles, so what we see, from the outer to the inner edges, is a progression of red, orange, yellow, green, and blue.

The sudden appearance of this rainbow, especially as a shaft of light emerging from a storm cloud, feels mythological. Interpretations of rainbows vary across cultures. In Greek mythology, rainbows symbolized a bridge connecting heaven and earth. But what moved me most was the story of individuals reaching full Buddhahood. Described as self-liberation from their physical bodies, those who attain enlightenment at the moment of death transform into a 'rainbow body,' a body of light that can appear anytime and anywhere when they direct their compassion.

moreShadow, Playa near Black Rock Point, Black Rock Desert, Nevada

Tectonic forces beneath the Earth's crust shaped the corrugated topography of the Intermountain West from Mexico to Oregon. Uplift and subsidence folded the land, fracturing the crust and creating alternating mountain ranges and basins, including Nevada's Black Rock Desert.

This basin contains silts and clays deposited by Lake Lahontan, which once covered much of Nevada. The lake reached its largest extent 12,700 years ago near the end of the last Ice Age, with its shoreline standing five hundred feet above the current surface of the desert. Over time, it gradually vanished as a warming climate reduced its size. Eventually, the lake evaporated into a flat plain. Bone dry most of the year, during winter and spring, rain and snowfall sometimes coat its surface with a thin layer of water teeming with fairy shrimp, providing habitat for migratory birds and making it impossible to cross on foot or by vehicle.

I took this photograph in a small playa separated from the surrounding desert by the Black Rock Range. As the late-day shadow lengthened from the elevated rim on the western edge of this one-square-mile desert bed, it stretched until it intersected with my spectral shadow. Surprised, I marked the spot, recorded the time, returned the following evening, set up my camera, and exposed the film when our shadows overlapped again. Two meditative figures wandering along the far edge of the playa below the rising moon offset the scene's symmetry. In the early evening, everything seemed to move slowly – the air, the sun, the moon, the drifting people; all except the shadows, which raced across the silent desert floor.

moreCanyon of the Yellowstone River, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

“The whole land seemed restless and alive,” summarized naturalist Edwin Way Teale upon experiencing the volcanically active Yellowstone National Park. Named after the colorful rock of the park’s river canyon, the indigenous Minnetaree called it Mi tse a-da-zi, which Lewis and Clark translated as Yellow Stone during their 1806 return trip through the river's lower reaches. However, neither the Minnetaree nor the Lewis and Clark Expedition traversed the plateau region that includes the Canyon of the Yellowstone River.

The 1,200-foot-deep V-shaped canyon was carved by river flow rather than glaciation, which is more common for canyons in this high-altitude northern region. Just 12,000 years old and formed after the last ice age, this canyon is rapidly eroding. A geyser basin previously located in this area transformed rhyolite left by lava flows. As a result, the rock became soft, brittle, and more vulnerable to erosion; it also rusts, creating a spectrum of warm-toned colors. Ecologist Kristen Prinzing pointed out that this wild, undammed river is the "last river in America that Lewis and Clark would still recognize."

When first visiting the park in 1980, I had recently stopped photographing with black-and-white film and switched to color, which seemed the perfect choice given this subject matter. From my precarious perch on the canyon's rim, I could hear the echo of the 300-foot Yellowstone Falls a mile upstream, loudly plunging into the ravine, with the river rushing down its steep slope beneath me through a narrow channel. Although I was eager to photograph the falls, when I turned around, my attention was captivated by the surreal, otherworldly colors of the canyon walls.

morePaulina Creek, Oregon

Central Oregon’s Paulina Creek plunges over an 80-foot waterfall, draining water from Paulina Lake, which lies within a caldera—a basin formed after the collapse of the Newberry Volcano that first erupted 600,000 years ago. The creek begins at a gap in the caldera’s rim, and its path was shaped by floods that carved a channel through the volcanic rock from past eruptions.

Today, magma beneath the caldera heats springs under the lake and around its edges. The lake’s flow into the creek is mainly supplied by inflow from these hot springs. Over time, soft layers of volcanic tuff beneath the waterfalls have eroded quickly, creating a chaotic pile of boulders at the base of the falls. Along the creek, limbs cut from lodgepole pines are scattered across the streambed, leftovers of forest thinning to lower fire risk and disease.

The caldera has been a site of intermittent human activity for 11,000 years. Upstream, near the top right corner of this photograph, lie the remains of the oldest known dwelling in the western United States- a 9,500-year-old summer camp. It served as a base for generations of the Windust people, mobile tribes of hunter-gatherers who stalked bison and elk and collected fruit and nuts from these highlands. That is, until Mt. Mazama (now Crater Lake) erupted a hundred miles to the southwest, covering the region in thick ash 7700 years ago. After that eruption, the basin was uninhabited for nearly 4,000 years, until native people visited the crater’s obsidian fields to knap arrowheads. Today, campers gather along the basin’s two lakes to fish, hike, and relax in its hot springs.

moreToe of Saskatchewan Glacier, Columbia Icefield, Alberta, Canada

Formed 240,000 years ago, the Columbia Icefield spans a 10,000-foot-high plateau atop the provincial border between Alberta and British Columbia. It is the largest icefield in the Rocky Mountains and the source of several glaciers. The Saskatchewan Glacier is the largest among them, extending eight miles and dropping a mile in elevation to its terminus.

The glacier’s size has fluctuated, expanding and shrinking due to changes in the climate. After the last ice age, the Saskatchewan Glacier reached its largest extent in the 19th century. Since then, its toe has retreated a mile, and in recent decades, its volume has decreased by about one percent annually. At one time, the glacier scraped against the base of the cliffs at the top of the photograph, three hundred feet above its current surface. Today, melting ice exceeds snow accumulation, causing trees, animal remains once trapped in the glacier, and rocks, sand, and clay to be deposited at its toe. At its current melt rate, the glacier could disappear entirely within another century.

Hiking alone to the glacier’s terminus, the remote and vast terrain seemed overwhelming. I felt small, vulnerable, and initially questioned whether it was wise to proceed. Navigating the trailless valley, I followed a thundering river, scrambled over and around boulder piles, and climbed unstable slopes until I reached this elevated view. What struck me most in this mid-summer scene was the sound of water: multiple water channels flowing on top of, and originating from, the glacier's base, flooded a silt-filled pond; the source of the Saskatchewan River, which then flows 1600 miles eastward to Canada’s Hudson Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

moreSheaves Cove, St. George Bay, Port au Port Peninsula, Newfoundland, Canada

The Port au Port Peninsula lies along the ancient Appalachian Mountain range, which stretches from Alabama to the Canadian province of Newfoundland. The peninsula extends into the Gulf of St. Lawrence from the rest of the province’s west coast through a narrow isthmus. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Basque fishermen, who had maintained seasonal fishing settlements for centuries, first called the area the Port of Rest. As year-round settlements developed, Port au Port became home to a mélange culture of bilingual residents from Mi'kmaq, Acadian, Basque, and French backgrounds. Since the 18th century, it has been informally known as the "French Shore."

Although the peninsula lacks natural harbors, Sheaves Cove has served as a sheltered beach where motor dories can be pulled ashore. Partially protected by a rocky headland, this cove is filled with palm-sized stones that shimmer in the midday sun through the clear, rippling seawater. These multicolored cobbles were formed from a complex geologic history of limestone, sandstone, and shale. They have been clamorously shaped by scraping and polishing against each other through the churn of ebbing and flooding swells. Light shifts from the sun's angle to a more vertical direction as it passes through the water. In this photograph, the water’s surface acts like a liquid lens, bending the light to magnify and distort the rounded stones. The various refractions outline and continually reshape their edges and faces as the rhythmic surges of waves from St. George Bay create a pulsing dance of light.

moreTwin Lakes Basin, Crystal Range, Desolation Wilderness, High Sierra, California

The Desolation Wilderness is a granite plateau in the northern Sierra Nevada Range, rising above the western edge of Lake Tahoe. As Kim Stanley Robinson wrote in his book The High Sierra, A Love Story, "Desolation expands after you enter it… The lack of soil created since the last ice age means it's still mostly rock, its scattered trees isolated, small, wind-sculpted."

Few hikers ventured up the trail on this mid-June day. As I climbed, I emerged from the forests at 7000 feet above sea level and entered a strange world I hadn't experienced in many years, where the air was thin and the sky a deep, dark blue. Pockets of plants lined the trail, and fast-moving streams collected snowmelt from surrounding peaks. The spare, expansive space felt almost lunar. Its openness and flat granite slabs made hiking easy, and with the incredibly clear air, the boulders, cliffs, and high rim seemed closer and more attainable. Cold in the shade and hot in the sun, the air became thinner with each step. By the time I reached the trail's end in this vast basin, there was 25% less oxygen to breathe.

At the tree line, life thrives, but the 'standing dead' persist as a reminder of the high country's fragile balance between growth and decay. Enveloped in light, the sun reflected brightly—almost harshly—off the pale granite and glowing snowfields. In 1894, naturalist John Muir described the Sierras as "the range of light…a vast wilderness in a sea of light." Amid the vastness and isolation, this remote corner of California offered a rare and soothing reprieve—a quiet sanctuary in a populous state. Feeling restorative, solitude became a welcome companion.

moreCoyote Buttes, Vermillion Cliffs, Utah

Two hundred million years ago, along what is now the border between Utah and Arizona, enormous dunes shaped by shifting winds migrated across a landscape dotted with oases that provided water and food for several types of three-toed dinosaurs. These cross-bedded dunes solidified into the Jurassic Navajo Sandstone and, after being uplifted a mile by tectonic forces, have since eroded into the striking landforms of Coyote Buttes.

Over a thousand dinosaur tracks are imprinted in the rock, overrun by the sandy footprints of hikers exploring this exotic environment filled with bewildering formations. In the late 1980s, a friend at Utah’s Canyonlands Field Institute suggested I visit the buttes to discover a terrain few knew about—a destination reached by crossing open country near the slot canyons of Buckskin Gulch. At that time, the red rock country was far less explored, with its remote wonders accessible by following deeply rutted four-wheel drive routes, far from major highways.

I was the sole visitor when I first discovered these buttes, though I approached with trepidation as I encountered the fragile sedimentary rock. Time and wind had worn their edges into delicate fins that could barely withstand being touched, let alone hiked on or climbed over. Swirling ribbons of color, formed by the oxidation of minerals like iron and manganese into thin, striped bands, began to attract attention. Published photographs started showcasing this landscape’s surreal beauty, drawing in more visitors. To help mitigate the danger of irreparable damage to the brittle formations, today, visitors apply for a limited number of daily hiking permits and are asked to follow hiking protocols.

moreMoraine Lake, Valley of Ten Peaks, near Banff, Alberta

Moraine Lake was eerily still when this photograph was taken on the evening of the summer solstice, just before midnight. The snow-covered slopes of the Canadian Rockies surrounding it were faintly mirrored on its surface, their reflection partially absorbed by the translucent water. The lake appeared otherworldly, emanating an unnaturally radiant glow in the enduring twilight that replaced night at this high latitude as it began transitioning into the next day’s dawn.

The glacially-fed lake reaches its highest level in late June, and when full, it iridizes a stunning azure blue. This unique color arises from refracted light off the rock flour, the dust sheared from glacial debris while suspended in the lake. Composed of silt-sized particles of quartz and feldspar, these particles are small and light enough to remain buoyant when the water maintains a consistent temperature of around 40 degrees. At this temperature, the water is most viscous, supporting the suspension of rock flour much longer than if the water were warmer or colder.

Named by Walter Wilcox in 1899 while mapping the Canadian Rockies, he wrote of Moraine lake, "No scene had ever given me an equal impression of inspiring solitude and rugged grandeur.” Later, it became clear that the lake was not formed by depositing a terminal moraine from an ancient glacier. Instead, a large, haphazardly piled hill of rocks and boulders dammed the lake as a result of one or more landslides, either transported to this location atop a glacier or, more likely, slid down from the Tower of Babel, a nearby peak. This accumulation of stones rose so high that it provided an elevated view of the lake.

moreDecaying Ponderosas, Fremont Point, above Summer Lake, Oregon

Hiking along the lofty rim of Winter Ridge, I felt as though I was perched high above the desert landscape surrounding southern Oregon’s Summer Lake, 3000 feet below. The view had a dizzying effect on me, much like it did on John Fremont, a western expedition leader who camped with his team on December 16, 1843, at the edge of this escarpment. He wrote, “At our feet–more than a thousand feet below–we looked into a green prairie country, in which a beautiful lake, some twenty miles in length, was spread along the foot of the mountains, its shores bordered with green grass. Just then the sun broke out among the clouds and illuminated the country below; while around us the storm raged fiercely… Shivering on snow three feet deep and stiffening in a cold north wind, we exclaimed at once that the names of Summer Lake and Winter Ridge should be applied to these two proximate places of such sudden and violent contrast.”

Fremont was correct in every aspect, except for the elevation relief, which is three times greater than he stated. Fremont Point is the highest elevation along the crest of this fault-block mountain. Looking east, it overlooks a deceptive landscape where distant views appear close, and its cliffs and lakes resemble miniatures. Near at hand, today’s rim trail is alonf an infrequently visited and extraordinarily beautiful ridge blanketed with wildflowers, sagebrush, ponderosa pines, aspens, and grassy meadows. The dead trunks and branches in this photograph are remnants of long-lived ponderosas. The cause of their demise is a matter of conjecture, though it is likely the result of a wildfire, bark beetles, drought, old age, or a combination of these factors.

moreSpring Runoff, Shoshone Falls, Idaho

In 1868, while leading a government geological expedition in southwestern Idaho, Clarence King remarked upon first beholding Shoshone Falls: "You ride upon a waste. Suddenly, you stand upon a brink. Black walls flank the abyss. A great river fights its way through the labyrinth of blackened ruins and plunges in foaming whiteness. Nor does the flashing whiteness brighten the aspect. In contrast with its brilliancy, the rocks seem darker and more wild."

Plunging 212 feet, the falls formed approximately 14,000 years ago from a cataclysmic flood originating from Lake Bonneville, which once occupied the same basin as today’s much smaller Great Salt Lake. The flood carved through southern Idaho's volcanic landscape within weeks, shaping the Snake River Canyon. The floodwaters struck a hardened layer of pink-gray rhyolite, resulting in a natural dike that created the falls. Located one thousand river miles from the Pacific, it once marked the limit of migrating salmon and the fishing grounds for the Shoshone ("salmon eating") people before the construction of downstream dams.

The river, which originates on the western side of Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, flowed at a robust 14,000 cubic feet per second on the day this photograph was taken, showcasing a cascading sweep of water typical for early June. On the opposite side of the river from this overlook, a dam situated just above the falls diverts some of the river’s water to a hydroelectric plant at the base of the falls. Every year, as the summer growing season progresses, upstream diversions for crop irrigation reduce the flow to a mere trickle between the gaps in the cliffs.

moreHead of Sinbad, San Rafael Swell, Utah

The Head of Sinbad is the highest point on the San Rafael Swell, a large plateau in central Utah, rising a mile and a half above sea level. Here, pale yellow-gray limestone from ancient marine life elegantly erodes its cliff faces. Creeks and streams radiate from the summit, flowing in every direction. Standing at its crest, I enjoyed a 360-degree view, surveying buttes, canyons, and distant ranges.

Although a short distance from Interstate 70, which bisects Utah and is within earshot, this location is only accessible via a rough four-wheel-drive path that winds through junipers, pinyon trees, and sagebrush. Just out of sight and to the right of this scene lies a shamanistic rock art panel (Barrier style) painted by hunter-gatherers who traversed this territory thousands of years ago.

A 1941 WPA guidebook to Utah credits the name "Sinbad" to Mexican traders who transported goods by mule train along a mid-1800s trail connecting Santa Fe and Los Angeles. The early 19th-century revival of Moorish architecture influenced what those travelers observed. The sight of the pillars, cliffs, and buttes along the route through central Utah's swell left an impression of "arabesque monoliths of multiple shapes and colors" representing "scenes or castles described in the Arabian Knights," according to the guidebook. While one might envision the rain-sculpted features of the cliff as having once been a castle's fallen peaked turret or the remnant of an ancient column, I see in its natural architecture something even more ancient: Jordan's city of Petra, which began construction in 150 BC by the Nabataeans out of and into its sandstone cliffs.

moreWhale Cove, Lake Tahoe, California

Around the summer solstice, when the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, sunlight penetrates deep into Lake Tahoe, enhancing the blue hues of its depths. Even in the shallows of Whale Cove on the lake’s eastern shore, the water’s luminosity differs from other times of the year. In winter, the low sun merely skims the lake's surface. In late spring, when the sun is directly overhead, as shown in this photograph, the lake's floor appears vibrantly colored. The rounded boulders that breach the surface almost seem to float.

Whale Cove derives its name from a large boulder located to the right of center that resembles a whale emerging from the lake with its broad mouth open. To the left, a motor skiff is anchored, and swimmers dive into the clear, chilly waters from its stern. A couple of visitors linger on the warmer shore to the right, soaking up the intense sun at this elevation of 6,000 feet. Others are tucked away in the shade of overhanging ledges, enjoying a book, meditating, or engaging in idle conversation.

The landscape was shaped by the surrounding ranges that rise several thousand feet above the lake. The Sierra Nevada Range to the west and the Carson Range to the east cradle the lake. Between these two ranges, the land’s subsidence and a volcanic tongue of lava damming its northern end have allowed snowmelt to fill the basin. The lake drains through a low point as the Truckee River, which then flows into Nevada’s Great Basin and empties into Flathead Lake before evaporating into the desert air.

moreYampa River near Confluence with Green River, Colorado

Mirrored in the Yampa River, a 1,500-foot butte overlooks the convergence of two major tributaries of the Colorado River, marking the northern boundary of the red rock canyonlands. It is here, in Colorado’s northwest corner, that the green-blue waters of the Green River, cleared of its sediment by an upstream dam in Flaming Gorge, merge with the coffee-colored waterway of the free-flowing Yampa, the last of such rivers in the West. At this point, the converging rivers blend before being carried downstream by the current.

On June 17, 1869, after navigating a treacherous series of upstream rapids on the Green River, explorer John Wesley Powell camped with his crew at Echo Park, an open stretch of cottonwood trees and a large field of grasses adjacent to the confluence, marking a stop before their heroic passage through the Grand Canyon. In the shade of the same grove (if not all the same trees), my wife and our young children camped 123 years later. A few years later, the embankment gave way as the river changed course, eliminating the campsite and the grove.

In the late 19th century, Butch Cassidy and his infamous Wild Bunch passed through Echo Park as one of the stops along a series of escape routes and hideouts known as the Outlaw Trail. In the 1950s, Echo Park became the focus of a proposed dam just downstream from this confluence, which would have flooded portions of both river canyons and Echo Park. The resulting political battle led Congress to explicitly prohibit the construction of dams in national parks and monuments.

moreEbb Tide, Cousin's Shore, Prince Edward Island, Canada

Garry Winogrand once said, "I photograph to see how something looks photographed." Like Winogrand, I often wonder how what I see through the viewfinder will translate into a photograph. Standing on the tranquil north shore of the Canadian Maritime province of Prince Edward Island, I set my view camera on its tripod and made a long exposure, contemplating how the sea might be rendered as it rhythmically lapped against the beach.

The resulting image gives the impression that time has stopped; everything seems perpetually fixed in place. That day, as I lingered on the beach, the sky cleared, the wind picked up, and the waves grew. However, for the most part, my memory has been replaced by the image itself; its enduring serenity has persisted for 50 years. The Bay of St. Lawrence appears to bulge slightly, with the light-toned ocean stilled by a brief period of calm along its near shore, while the darker tone just below the horizon depicts a brush of wind.

Sometimes the image is so spare that it could have been made anywhere. But upon closer examination, it features a few subtle characteristics unique to that location. The flat, granular evenness of the beach’s surface is indicative of a shore long worn down to sand and pebbles. Tides change little along this coastline, diminishing the size of waves on the incoming tides. Highlighting the flatness of the Bay of St. Lawrence, particularly along Prince Edward Island’s north shore, prevailing winds blow seaward, revealing an ocean shaded by the wind only where it strikes far offshore.

moreSun Dog, Bristol Dry Lake, Mojave Desert, California

Driving through the Mojave Desert in southeastern California, I passed through a wild, open country dotted with abandoned truck stops, motels, and restaurants along old Route 66, now supplanted by nearby Interstate 40. Outside Amboy – a town surrounded by cinder cones, mountain ranges, and dried salt beds – I came across National Chloride, a salt mining operation. In the late winter afternoon, I pulled over to admire the vibrant sky above Bristol Salt Lake.

This brackish lake formed in a depression that collects salt-rich sediments from the surrounding mountains. Unlike other western desert lakes during the Pleistocene era, when the climate was cooler and wetter, the playa has never filled with water. However, after rare rainstorms, it is covered by a shallow pool. Dissolved halite (rock salt) circulates within the water table just beneath the lakebed, fueled by the magma heat of this volcanic region. First extracted here in 1858, salt mining and, more recently, the active development of lithium extraction continue.

Sundogs are a type of halo, an optical phenomenon created by the interaction of sunlight with cirrus clouds composed of ice crystals that float horizontally in the atmosphere. They refract light horizontally, producing red, white, and blue spots to the right and left of the sun (thick clouds obscure the left sundog). Also called ‘phantom suns,’ they can be generated by moonlight and may occur on other planets. They are more common in specific locations on Earth, such as the Mojave Desert, where the sky is often filled with cirrus clouds.

moreSlickhorn Canyon, near San Juan River, Utah

A mile upstream from its confluence with southern Utah’s San Juan River, Slickhorn Canyon shelters an alcove teeming with plants and wildlife. Eight-hundred-foot cliffs shade and protect a pool along a creek fed by spring snowmelt and summer monsoon downpours.

Slickhorn’s talus slopes and rockfalls clutter its gulch with boulders, bordered by cottonwoods and junipers. Flat blue-gray rock, a blend of sandstone and limestone, paves the canyon floor in a series of shelves that stair-step down to the river, fed by a meandering stream and interspersed with occasional oases formed in shallow depressions on the shelves. Like its indigenous wildlife, hikers depend on these pools to fill their bottles as they venture up the canyon from rafting campsites along the San Juan River. Others trek down from the canyon’s upper rim to the river, passing ancient Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings and painted and carved depictions of people, animals, and abstract designs on the canyon walls.

At this location along the ravine’s lower end, shale has fractured into perpendicular blocks compressed by the weight of the overlying rock. Undercut by erosion and cleaved from the cliff, the slab in the photograph’s center careened down a steep slope, coming to rest alongside this verdant pond. Coating the exterior surface of the encircling walls are dissolved particles of iron oxide and hematite, trickling down to create a red, yellow, and brown veneer that contrasts with the pale rectangular boulder. Its white, unvarnished glow suggests that it was only recently excavated from the wall above and will, over the next few hundred years, begin to blend with the canyon’s stained walls.

moreKe' e Beach, Kauai, Hawaii

At the end of the road along Kauai's north shore lies a beautiful and popular beach, surrounded by a wilderness of high mountains that meet the shore along a narrow fringe of sandy white beaches. From May to September, an offshore reef breaks the waves, protecting the foreshore's tranquil turquoise swimming pool of seawater. This beach becomes increasingly hazardous from October to April as the easterly trade winds shift to a northerly flow, bringing dangerous currents and high waves that overrun the reef and erode the beach.

Evidence of this erosion is the exposed roots of Casuarina trees on the beach terrace. As I approached the beach, this tree caught my attention as it almost seemed to hover in the air, its tethered roots anchored to the ground. Though they might appear indigenous to Kauai, the non-native Casuarina trees were planted in the 1870s as windbreaks. They thrive in the shoreline's saline soil, grow rapidly, and have a short lifespan. After planting, they invade an area, edging out other plants by emitting toxins that prevent them from taking root, leaving the ground bare beneath their thick canopies.

In addition to damaging winter storms, rising sea levels are expected to submerge 90% of the island's beaches by 2100. Kauaians are comprehensively addressing these threats and the growing impact of tourism on beaches. For example, they have closed Ke 'e Beach to vehicles and instead provide bus service as one step in implementing a series of island-wide measures to mitigate these effects on their population, nearly all of whom reside along the island’s vulnerable coastline.

moreEbb Tide, Elliott Bay, Puget Sound, near Seattle, Washington

South Beach stretches along Elliott Bay in the Puget Sound, extending from the Seattle neighborhood of Magnolia to the West Point Lighthouse in Discovery Park. Formed from sediment deposited by longshore currents, this silt- and sand-laden beach plunges just past the tidal zone to over 100 fathoms. On this late afternoon, evenly spaced waves broke with the regularity of a metronome, undulating in a slow-moving rhythm along the low tide line.

The surface and sounds of the bay are typically quiet. The fetch across the narrow sound is not long enough to create sizable or consistent breakers. “Puget Sound was known as "Whulge," an onomatopoetic Coast Salish word denoting the sound of waves. If you listen closely, the waves washing against the Puget Sound shoreline make a subtle sound. It is not the booming surf of the outer coast but something unique to our region. The quiet, persistent sound of an inland sea," wrote David B. Williams in his book "Homewaters.”

However, large, fast-moving container ships often steam past South Beach as they head to or depart from the Seattle shipyards. The energy generated by plowing through water from the ship's bow sends out trails of V-shaped waves. These ships produce waves of remarkable uniformity and size, lasting for half an hour and reaching 3 to 6 feet, large enough for a small group of Puget Sound surfers. As shown in this photograph, there are times when an oscillating swell created by wind and tidal currents courses diagonally to the ship waves, resulting in a geometric, rippling pattern called a cross sea, which creates a subtle moiré pattern.

moreSpring Melt, Grand Falls of the Little Colorado River, Arizona

Grand Falls in northeastern Arizona lies within a remote basin traversed by the Little Colorado River. The river originates from the snowy peaks of the White Mountains and is fed by natural springs along its 300-mile journey before merging with the Colorado River in the heart of the Grand Canyon. The river's flow varies in intensity and color with the seasons. Also known as "Chocolate Falls," during early spring, rainfall and snowmelt wash muddy sediment from tributaries, tinting the river ochre. An emerald-blue trickle, dyed by travertine-rich spring water, runs over the falls during dry spells.

At one time, my camera's location would have been 200 feet above a canyon that once served as the river's channel. When I took this image decades ago, I stood atop a lava flow that, 20,000 years earlier, had filled its historic gorge. The hard, impermeable lava forced the Little Colorado to carve a new route around the volcanic rock, causing it to cascade over a section of the canyon wall seen on the right side of the photograph.

Across the river, on a butte, lies the hillside letter "G," designating "Grand Falls." That has since vanished, along with the open road to the falls. In 2023, tribal residents closed the area. Like other ancestral sites in the West, rapidly increasing tourism has made places such as Grand Falls unsafe and unmanageable. The river sustains local agriculture and holds sacred significance for the ancient beliefs of the native population. Zuni farmer Jim Enote described the river as "an umbilical cord that connects us back to our emergence place, the Grand Canyon."

moreSteins Pillar, Ochoco Mountains, Oregon

Forty million years ago, a rapid series of eruptions released thick flows of volcanic pumice, ash, and dust that swept across the Ochoco Mountains in north-central Oregon. While still hot, these materials fused into solid rock. As the volcanic tuff began to erode, minerals within it leached over the rock, forming a thin, impervious coating that preserved outcrops of the formation and tinted them yellow and red. When the rock cooled, one section fractured and split into a long, slender column: the 350-foot-high Steins Pillar.

When I moved to Central Oregon, I encountered a landscape almost entirely covered in volcanic rock, so it was a surprise hiking to this immense column, which resembled the types of formation I used to explore in southern Utah's Bryce Canyon. Even the ponderosa pines appeared similar to those along Bryce’s trails, where, like here, they grow around the bases of rocky spires. However, Steins Pillar is not composed of eroding sedimentary rock. Instead, it is part of a long history of Oregon’s volcanic eruptions that shaped its mountains and created the lava flows that cover the high desert plains.

In the Ochoco Mountains, the underlying lava retains water, nurturing dense thickets of ponderosa and lodgepole pines that support a thriving population of deer, bobcats, black bears, and mountain lions. The monolith presides over the surrounding old-growth forest. Rock climbers have long attempted to scale its overhanging layers, grappling with pitons penetrating its hardened exterior, often losing their grip when embedded into the softer, chalky interior. Challenging and dangerous, it was finally summited in 1950.

moreTree Rubbings, Choprock Canyon, Escalante River, Utah

"There is poetry in everything if you look closely enough," observed artist Cy Trombly. Ancient cliffs border central Utah's Escalante River. The sheer walls chronicle their geologic history, recorded in a palette of tones, colors, and textures on the smooth surface of Wingate Sandstone. Initially, I couldn’t grasp what was at play, trying to parse the complexity of one inscribed wall’s patterns. Underneath its surface markings, layers of once-shifting ancient dunes are outlined in wavy lines. Desert varnish darkens the left side of this wall through an accumulation of minerals and bacteria interacting with sunlight and water. Thin, pale vertical rain streaks leave delicate drip marks down the height of the wall.

Finally, petroglyphs – markings and incisions formed not by human hands but by natural forces – were elegantly scraped and engraved onto the cliff wall. I wondered, "How were these lightly brushed and darkly engraved gestures created?" Observing the dead trunks and limbs of cottonwood trees beneath the wall, I realized that the limbs and branches, swaying in the wind, had produced these marks. It was something I had never seen before.

The convex-curved wall, arching forward in height, intersected with the growing limbs and branches of a cottonwood tree. This effect recalled Twombly's pencil and chalk drawings. As the wind shifted them, the thinner branches lightly brushed against the surface, while the limbs and thicker branches engraved the rock. Whether they are branches as extensions of a tree or a hand as an extension of an artist's eye and mind, both naturally create sweeping marks. As Twombly observes, "I am not interested in straight lines. I am interested in curves, irregularities, and accidents."

moreDrift Log, Rialto Beach, Olympic Peninsula, Washington

Rialto Beach is a mile-and-a-half-long stretch filled with driftwood along the northwestern coast of Washington. Sometimes described as a graveyard of trees, it possesses a brooding quality. On this quiet, cloudy morning, the misty shore is a chaotically arranged museum of wizened tree trunks and root balls. Each skeleton of wood, embalmed in salt and bleached by the sun, exhibits a rough-hewn grace, expressively rendering its final gesture.